Central and Eastern European Artists in Interwar Metropolises

nemzetközi konferencia

A vizuális művészetek aktuális trendjeinek, eszméinek és intézményi modelljeinek terjesztését mindig is a földrajzi és kulturális határokat tartósan vagy ideiglenesen átlépő szereplők tették lehetővé. A konferencia a Közép- és Kelet-Európából származó képzőművészeknek a metropoliszok felé irányuló migrációját vizsgálja a két világháború közötti időszakban. E mozgások jellemző sémákat követtek: a hivatalos művészeti oktatásban részesülő művészek képzésének része lehetett a tanulmányút, amelyet különböző ösztöndíjak segítségével finanszíroztak; másokat politikai rezsimváltások kényszerítettek hazájuk hosszabb-rövidebb távú elhagyására. A művészek többsége külföldön támaszkodott formális vagy informális, személyes, szakmai vagy politikai hálózatokra.

A kényszerű vagy önkéntes, ideiglenes vagy állandó nyugati tartózkodások, az ezekhez az időszakokhoz köthető művek, műcsoportok, alkotói periódusok értelmezése mellett Forgács Éva (Art Center College of Design, Pasadena; Moholy-Nagy Művészeti Egyetem, Budapest) és Angela Lampe (Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou, Párizs), valamint hat különböző országból érkező résztvevők előadásai bemutatják, hogy a művészképzés hagyományos intézményei, politikai mozgalmak, értelmiségi csoportosulások körül sűrűsödő hálózatok, vagy az informális, családi, baráti kapcsolatok miként biztosíthatták az alkotás és megélhetés feltételeit a művészek számára.

Az absztraktfüzet ide kattintva letölthető.

Az előadók névsora ezen az oldalon olvasható.

![]()

Galéria

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 10.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

• 2024. 10. 11.

Programok és videók

2024-10-10

| Időpont | Cím: absztrakt/videó | Előadó |

|---|---|---|

| 09:15 - 09:30 |

Regisztráció

|

|

| 09:30 - 10:00 |

Köszöntő

Petrányi Zsolt, tudományos főigazgató helyettes, Szépművészeti Múzeum - Magyar Nemzeti Galéria Fehér Dávid, KEMKI igazgató Gucsa Magdolna és Őze Eszter, KEMKI |

|

| 10:00 - 12:10 |

Session 1 · Women, Class and Labour Movement

Szekcióvezetó: Nagy Kristóf |

|

| 10:00 - 10:20 |

Adornment as a Matter of Class: Émigré Women Fashion Jewellery Designers in Paris (1920–1930)

The case study of women émigrés from the former Russian Empire adorning Parisian haute couture in 1920–1930 is of great interest, not so much for the transfer of ethnic ornamental motifs (Albertini, Kurkdjan, 2023) as for the association of ornament production with social downgrade. However, the bourgeois-educated women under discussion have nothing in common with the tragic destinies of white emigration, fallen to the rank of fabric workers and servants as a consequence of exile. Quite the contrary: they successfully integrated in the Parisian artistic and intellectual scene. Sympathizing with the European socialist movements, and not yet excluding returning to their home countries, they helped to build a connection with the Eastern European avant-garde. Even though driven to manual work by economic necessity, they created costume jewelry to be sold by the most famous Parisian fashion houses. Made from non-precious materials, simple but formally inventive, these adornments took fashion closer to contemporary artistic practices. Disputing the political potential of decorative arts with the artistic spheres of their male companions, like literature and visual arts, the ornaments created by Eastern European émigrés took part in the development of modern aesthetics. Unlike traditional craftsmanship, it sought to overturn the existing class relations. Éli Lotar’s photograph of Elisabeth Makovska, adorned with a necklace made by Elsa Triolet, gives us a glimpse of the network to reconstruct. Did these women designers perceive as downgrading the work of adorning local bourgeoisie and aristocrats, who constituted the major part of their clients, or on the contrary, were they fulfilled by the connection with the working class they earned? How do those commercial relationships enable the class enemies in their homelands to socialize in exile? Could those women decorators seek to spread this political ambition of adornment to their countries of origin? |

|

| 10:20 - 10:40 |

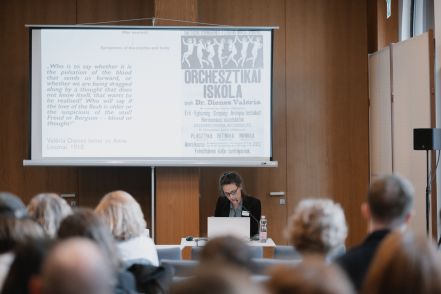

Female Body Culture and the Concept of Labour in the History of the 20th Century Hungarian Avant-garde

In my talk, I examine the gendered aspects of emigration and cultural production in the left-wing Hungarian avant-garde. As a case study, I deal with two women-led avant-garde movement art institutions in the interwar period. The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary (1919) had a great impact on the Hungarian avant-garde art scene: after its fall, several artists who had taken an active part in the organisation were forced to emigrate. In addition the government almost completely eliminated the possibilities for a formal left-wing movement, so collective “leisure” activities became prominent areas of political organization, like the movement art. The movement art schools run by Valéria Dienes and Alice Madzsar were important institutions of the Hungarian life-reform movement and also the leftist field of the interwar period. Madzsar studied in Berlin in the early 1910s, Dienes in Paris at the same time, while later in the 1920s both shared the experience of emigration after 1919: Dienes moved to Vienna and then to Paris, while Madzsar supported her husband, József Madzsar, who fled to Vienna. I will examine these two periods: I will show what opportunities and possible life paths were open to these women artists when they were acquiring their emigration experiences. I will examine two forms of emigration: on the one hand, I want to understand the migration of knowledge, and on the other hand, I want to understand how we can broaden the concept of emigration and, through this, better understand what it meant to be an emigrant between the two world wars. While I present the two movement art schools, the theoretical approach of my paper places the woman’s gymnastics and movement art schools primarily within the wider processes of the institutionalisation of the world of work and of the emergence of industrial capitalism. |

|

| 10:40 - 11:00 |

Kati Horna on the Horizon of the European Left-Wing Movements

Kati Horna, or by her maiden name Kati Deutsch (1912–2000), is one of the Hungarian-born photographers who left their country for good in the interwar period. In the two decades since her death, Horna’s oeuvre has become the focus of much international research, but her name is still almost unknown in her native country. Kati Horna raced through the metropolises of Europe (Budapest, Berlin, Paris) and civil war-ravaged Spain until the age of twenty-seven, only to arrive in a new continent, and begin rebuilding her life in Mexico City. Her life story can be defined as a model of artistic existence organised on the basis of worldview, so I approach the subject from the perspective of her career arc, one that unfolded entirely in emigration. My research focuses on the motivational factors and identity-forming influences that played a decisive role in her choice of emigration destinations and influenced the development of her art. The subject of my research is the rich intellectual horizon that traces the background of her oeuvre through the defining intellectual-political currents, as well as through a web of relationships woven by exceptional individuals. An important point of her orientation was the experience of the culturally based opposition movement and the progressive political and intellectual atmosphere. Deutsch grew up in as a teenager in the Munka (Work) Circle and later in the Oppozíció (Opposition). The intellectual milieu during her time in Berlin included the liberal-minded institution of Deutsche Hochschule für Politik, the seminars of the German critical Marxist philosopher and close friend Karl Korsch, as well as the cultural gatherings at Bertolt Brecht’s apartment. The influence of Korschist views transmitted from Berlin to Hungary by Kati’s first husband, Pál Partos, is an important but little known episode in the history of ideas, and one that is thus illuminated from an unusual narrative. Her time in Paris and during the Spanish Civil War shows that her engagement and transnational solidarity led her to take an active role: she published her photographs and montages made with her second husband, José Horna, in antifascist and anarchist magazines. In my lecture, I will use intellectual history and network research considerations to explore how the extremely broad spectrum of these radical communities and left-wing political thought, which can be traced in her immediate environment, influenced her development as a photographer. |

|

| 11:00 - 11:20 |

Sensitive Female Universes: Considerations on the Work of the Hungarian–Brazilian artist Yolanda Mohalyi

In this paper, I will address the case of the Hungarian-Brazilian painter Yolanda Mohalyi who occupies a lonely place in the historiography of Brazilian art since, on one hand, she is undisputedly an icon of Brazilian informalist painting, and on the other, monographic studies dedicated to her work are limited to reporting art criticism of mid-twentieth century. Mohalyi’s initial artistic training took place in an artist colony in Nagybánya, which brought together people interested in Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, among other avant-garde movements. She then studied at Budapest’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1920s. Immigrating to Brazil in 1931, she settled in São Paulo, where she met a Jewish expressionist artist from Lithuania, Lasar Segall, who had been part of Brazil’s modernist movement since the 1920s. This friendship helped Mohalyi become integrated in the local scene. In the late 1950s, Mohalyi immersed herself in Art Informel, for which she is known today, and received several awards until her death two decades later. To comprehend Mohalyi’s trajectory as an emigree I will use recent feminist approaches that focus on the Jewish-Romanian-American artist Hedda Sterne, whose abstract expressionist work, little studied until the 2000s, is of great interest today. Sterne also had academic and avant-garde training in her native land, before emmigrating to the US in 1941. Sterne’s current rehabilitation as a key artist of the abstract expressionist setting offers an understanding of Mohalyi’s artistic position too, given their involvement in similar dialogues with mid-twentieth century abstract painting, and their subsequent insertion in artistic scenes in the Americas. |

|

| 11:20 - 11:40 |

Mapping Multiple Modernisms: The Question of Emigration in the Lajos Kassák – Jolán Simon Research Project

Avant-garde historiography has long focused on the activities of émigré artists of the 1920s, particularly artist-editors and their transnational visibility. Challenging some of the routines of art and literary history writing, our research project prioritizes the examination of cultural networking and the gendered aspects of labor division in the spheres of cultural production over individual achievements and emphasizes the social embeddedness of knowledge production, moving beyond the symbolic realm of imagined modernist communities. This presentation provides an overview of the four- year research project funded by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA), titled the “Digital Critical Edition of Lajos Kassák’s and Jolán Simon’s Correspondence Between 1909 and 1928, and New Perspectives for Modernism Studies”, focusing on its two primary objectives. Firstly, we delve into the digital humanities foundation of our project, detailing methodological considerations such as the use of the TEI XML markup language, digital facsimile and literal transcription of documents, metadata structure, and data enrichment techniques. Specifically, we explore how these methodologies aid in processing multilingual texts related to Kassák’s time in Vienna from 1920 to 1925 and mapping his transnational network using digital humanities tools. Secondly, we highlight the scholarly potential of avant-garde archives, particularly in preserving “traces” (as Aleida Assmann puts it) that may be considered marginal or invisible from the perspective of the artistic canon and mainstream interpretive trends. Beyond shedding light on the array of invisible labor through which Jolán Simon contributed to Kassák’s career, their correspondence also reveals Simon’s essential role in keeping their intellectual circle interconnected during the year of the emigration to Vienna. Additionally, by making the couple’s networking strategies visible, we can explore how working-class individuals, such as our protagonists, navigated the public sphere and eventually established their own counter-hegemonic milieu using avant-garde techniques in Austria and Hungary. |

|

| 11:40 - 12:10 |

Vita

|

|

| 12:10 - 13:15 |

Ebéd

|

|

| 13:15 - 13:40 |

Kávészünet

|

|

| 13:40 - 15:30 |

Session 2 · Nation/State, Subversity

Szekcióvezető: Tóth Balázs Zoltán |

|

| 13:40 - 14:00 |

State Representation of Hungary in Interwar Metropolises. Exhibition Design and the Foreign Trade Office

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Hungarian Foreign Trade Office was an important organiser of Hungary’s participation in international exhibitions. The main goal of their activity was to promote Hungarian export at trade fairs in economically prominent metropolises. The goods (agricultural products, crafts, etc.) on offer were promoted in historical and cultural contexts, with the aim of attracting the attention of the general public. “… abroad we must use the splendid wealth of forms, colours and decorations offered by Hungarian folk art to dress the propaganda tools of our Hungarian agricultural products in these clothes. Foreigners like the unique, the original, and they always stop when they see the unusual.” wrote István Radnóti (Propaganda Chief of the Hungarian Foreign Trade Office) in 1935. The pavilions, the interior design, the artistic decoration of exhibitions and visual materials ordered by the Office were frequently and highly praised by Hungarian press, such as the main journal of modern architecture: Tér és Forma (Space and Form), and the journal of the National Association of Hungarian Applied Artists: Az Iparművész (The Applied Artist). These two forums also symbolized the duality between modernity and the visuality of traditional rural: concepts, strongly defined the interwar image of Hungary. In my paper, I will examine the visual representation of Hungary through export exhibitions and try to identify the contributing artists and their relation to exhibition design. In addition, I will discuss the Export Exhibition (Budapest, 1938) held for the occasion of the Second World Congress of Hungarians, that thematized the topic of emigration. One highlight of the Export Exhibition was a large world map, decorated with stylised folk motifs, visualizing the quantity and location of the Hungarian diaspora, who were also encouraged to promote goods as their “national duty”. Like the other exhibitions of the Office, the map and the exhibition were designed by “distinguished” young Hungarian artists, whose work is almost entirely unexamined by previous research. |

|

| 14:00 - 14:20 |

Visual Language as a Socio-Political Tool. The Irreprehensible and Anti-Cosmopolitan Crusade of Štefan Prohászka (1928–1938)

Opened in 1995, Šamorín’s At Home Gallery was the opposite of the cultural nationalist policy of the new Slovak state. While in the 1990s state funds were used to promote “national interests”, the apartment gallery of this small rural town launched contemporary art projects that contradicted the rhetoric of the extreme nationalist government. Little by little, and thanks to the private gallery of this small town in the county, Šamorín was freed from the peripheral role to which the Slovak cultural policy wanted to condemn it. This desire to break out characterized the visual language of István Prohászka/Štefan Prohászka (Šamorín, 1896 – Mosonmagyaróvár, 1974). The exhibitions in Bratislava in 1928, Budapest in 1929, and Košice in 1936 conveyed to the cosmopolitan citizenry a visual message that interpreted the emphasis on small-town life and social tensions in this modernizing state as preparation for a long-term political program. The toolbox of Prohászka’s visual language still requires careful interpretation through several methodologies. He was a student of György Leszkovszky and Imre Simay at the Royal Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts. During this time, he spent several months in Germany, where he got to know the spirit of the Bauhaus, tasted Berlin’s cosmopolitan artistic milieu, and also embraced the spirit of the German left-wing movements. He was aware that the disintegration of the Austro–Hungarian Monarchy and the pre-war status quo of Central European societies would soon break down, and because of this, the artist not only assumed the role of an agitator but was also able to modify this fragile state with his involvement. Although the Budapest press tried to label him an unconventional and radically thinking artist, Prohászka’s diverse modernist stylistic language not only hid a political way of thinking but also reflected on the individual drama of social life and an intellectual struggling with a dual national identity. As a member of the “Sarló movement” and member of the editorial office of the left-wing newspaper Az Út, he actively participated in the creation of social and political movements. At the same time, Mária Lauer, an industrial artist and designer, joined the socio-photo movement together with his wife, to better understand the situation of the economically disadvantaged social classes. In my presentation, I will not only present the subjectivity of the artist as an “agitator”, but also the multi-coloured toolbox of his visual language, which made him unique within the Central European art milieu. |

|

| 14:20 - 14:40 |

Reuven Rubin and the Interrelations of Artist Sponsorships and Institutional Networks in New York City, 1921–1922

While convalescing from the war and struggling to find his artistic voice, the Romanian painter Reuven Rubin (1893–1974) traveled on his own volition from Czernowitz to New York City in 1920. This episode occupies a scant chapter in the scholarship on Rubin, which points mostly to his friendship with Alfred Stieglitz and his exhibition at the Anderson Gallery as the impetus for an artistic transition that would later reach maturity after Rubin immigrated to British Mandate Palestine in 1923. While analyzing his artistic development, my paper will focus intently on the overlooked sponsorships and financial support Rubin enjoyed from individuals and institutional networks in New York. In addition to revisiting the known support and friendship from Stieglitz and sponsorship by Romanian Ambassador Prince Antoine Bibesco, I will look closely at archival documents from the National Library of Israel, yet to be considered in the scholarship, that cast an entirely new light on Rubin as an artist and refugee in New York. For example, correspondences between Dr Judah Magnes and his social and intellectual circles in New York reveal collective efforts to purchase Rubin’s paintings at the Anderson Gallery and provide the artist with charitable support. Likewise, documents and correspondences from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee unveil efforts to secure Rubin’s transportation back to Romania amid controversial issues over his “refugee” status in America. The absence of this information in the literature, including Rubin’s autobiographical memoir, I argue, attests to the covert operation of these networks without Rubin’s knowledge. My paper contributes a new chapter on Rubin in New York and, in support of the conference objectives, expands the art historical discourse to address relationships between artists and their sources of funding such as networks centered on private and institutional support. |

|

| 14:40 - 15:00 |

City, Light, De-Coloniality and Artistic Subversivity

The intersection of “city,” “light,” and “de-coloniality” encapsulates a rich and multifaceted area of inquiry, touching upon themes of urbanism, power dynamics, and cultural representation. This opens up avenues for exploring questions of urban identity, representation, and social justice. It invites inquiries into how colonial histories have shaped urban landscapes, whose voices and experiences are privileged or marginalized in the city by imposing their own spatial planning and design principles on colonized territories, reshaping existing urban landscapes or creating new ones according to their needs and ideologies. Many cities in former colonies still bear the imprint of colonial spatial organization and light installation, with distinct areas designated for Europeans, indigenous populations, and other ethnic groups. Consequently, colonial rule often brought about the construction of architectural landmarks and illuminating infrastructure that reflected the power and prestige of the colonizers. This included government buildings, churches, palaces, and transportation networks built in colonial architectural styles. These structures not only served functional purposes but also served as symbols of colonial authority and cultural dominance. Colonial histories have left a lasting imprint on urban landscapes, shaping their physical form, social structure, and cultural identity. Understanding these legacies is essential for grappling with the issues of urban inequality, social justice, and cultural heritage in postcolonial societies. These matters can be approached by investigating artistic and cultural practices that challenge dominant narratives and reimagine urban futures. This lecture aims to identify artistic practices and productions that challenge dominant narratives in the interwar metropolis by reimagining urban futures, contributing to the creation of more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable cities. Starting from László Moholy- Nagy’s Dynamic of the Metropolis, I will reflect on artistic practices that might inspire collective action, foster empathy and solidarity, and offer new ways of seeing and experiencing the urban environment. Additionally, I will investigate artistic projects that might prompt considerations on how urban lighting practices and design can reflect and contribute to broader processes of decolonization and social transformation in cities. |

|

| 15:00 - 15:30 |

Vita

|

|

| 15:30 - 16:00 |

Kávészünet

|

|

| 16:00 - 17:30 |

Session 3 · Metropolis: Representing the Metropolis – Contemporary and Posterior Takes

Szekcióvezető: Gucsa Magdolna |

|

| 16:00 - 16:20 |

The Politics of Precision: Louis Lozowick’s Precisionist Cityscapes, 1923–1938

Ukrainian-born American artist Louis Lozowick (1892–1973) is best known for his precisionist cityscapes from the 1920s. Images like New York from 1923 exemplify Lozowick’s particular approach to the modern metropolis, which prioritizes crisp lines, sharp geometries, and a cubistic articulation of space. Yet, around a decade later, Lozowick had dramatically changed tack, and he adopted a hardened realism to represent the city. Storm Clouds Above Manhattan from 1935 demonstrates the remarkable shift away from the composite perspectives of cubism toward the insistently “traditional” linear perspective and an almost baroque naturalism that would come to occupy Lozowick for some time. New York and Storm Clouds Above Manhattan have in common both their medium and the metropolitan subject matter, yet the way they depict New York City, an emblem of urbanization and industrialization, is divergent and arguably even opposed. While Lozowick emigrated from Ukraine as a child and he proved a more committed and astute commentator than many of his leftist peers in New York City on aesthetic and political developments in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. This paper prioritizes the artist’s status as an immigrant, as well as his proximity to and interest in constructivism, the Neue Sachlichkeit, and socialist realism, in order to situate Lozowick’s developing vision of urban space within domestic and international debates, over the political efficacy of figuration and realism. It explores one interaction between artistic production, urban space, and leftist culture during what were to Lozowick simultaneous crises, namely, the Great Depression and the ascent of Stalinism. For decades, histories of European modernism have reckoned with the abandonment of abstraction and the following resurgence of figuration in the interwar period. The politics and modernisms of the United States remain, however, largely peripheral to these important and contentious questions. With an eye toward reconsidering the tangential position of the US, this paper evaluates the work of an immigrant artist whose work remains largely absent from extant art histories. |

|

| 16:20 - 16:40 |

László Péri, Alfréd Kemény and the Debate on Revolutionary Realism, Berlin, ca. 1928

Alongside graphic artists Sándor Ék (Alex Keil) and Jolán Szilágyi, and critic Alfréd Kemény (Durus), László Péri is counted among the Hungarian émigrés who, prior to assuming leading roles in the communist Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists (ARBKD) from 1928 onwards, were highly influential in disseminating both Hungarian and Soviet constructivism in postwar Weimar Germany. However, by 1928, the attitude towards constructivism and other forms of non-objective art had undergone a radical shift among the artists and critics affiliated with the KPD and the ARBKD. In 1929, Kemény stated that “an ‘abstract’ person can only recover if they turn away from ‘abstract’ art and return to being a person of flesh and blood.” This aggressive stance against non-objective art is, among others, directed towards the group of Berlin constructivists Die Abstrakten, of which Péri was a member. This group would later, in 1932, change its name to Die Zeitgemässen (The Contemporaries) to fully adhere to the demands of communist cultural politics. Kemény’s rhetoric already bears the marks of socialist realist denunciation of modernism, although Kemény would only fully embrace this position later. Just a few years earlier, however, Kemény, for instance, in a text on Péri’s linoleum cuts, had strongly advocated for a conception of non-objective constructive artwork as an “abstract reality” which, resisting bourgeois anarchism, represents the communist order of “proletarian world revolution” in its transitory period. My contribution aims to elucidate the shift and its repercussions for artistic practice by tracing the various stages in Péri’s work from the early 1920s to the early 1930s. I will argue that the political context of failed revolution and exile is reflected as much in the trajectory of his work as in the debates on revolutionary realism, both on an international scale (Comintern) and within the locally specific context shaped by the transnationalism of the modern metropolis, particularly Berlin. Against this backdrop, I will analyze Péri’s turn to figuration, his communist commitment — highlighting its zenith during his association with the ARBKD in 1928 — and his distinctive sculptural materialism. I argue that his embrace of “concrete” art (both in terms of its representational realism and its material) — offered an alternative to the ideological dichotomy between abstraction and figuration by linking the artwork materially to the modern industrial metropolis. |

|

| 16:40 - 17:00 |

Exhibiting Emigration. The Case of the Modern Magyar Exhibition

The exhibition Magyar Modern – Ungarische Kunst in Berlin 1910–1933 (Modern Hungarian – Hungarian Art in Berlin 1910–1930) presented the work of Hungarian artists working in Berlin in the first third of the 20th century. The exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie was organized in cooperation with the Museum of Fine Arts – Hungarian National Gallery from November 2022 to February 2023. The exhibition focused on artists and works of art directly related to Berlin. This was defined on the basis of three criteria: the artist had to have been a resident of Berlin for a certain period of time and/or the work had to have been made there and/or it had to have been exhibited in Berlin. These criteria led to the inclusion of well-known artists and emblematic works, as well as lesser known or little known artists, sometimes with works that we did not even know existed. Previous exhibitions with similar aspects have focused on Hungarian artists in exile in Germany (e.g., Wechselwirkungen, Kassel, 1986–87), with a particular emphasis on artists associated with the Bauhaus. In my presentation, I will introduce the “Magyar Modern” exhibition, describe its concept and the path leading to its realization, as well as the questions and new discoveries that have inspired us to further research this topic. I will also discuss the catalogue of the exhibition, which is structured in accordance with the logic and structure of the exhibition, with each essay being linked to a chapter of the exhibition. |

|

| 17:00 - 17:30 |

Vita

|

|

| 17:30 - 18:00 |

Kávészünet

|

|

| 18:00 - 19:00 |

Keynote Lecture: Challenging National Art Histories

The main point of examining the new situation in the international art world caused by the emigration of many artists in the wake of World War I, is the questioning of the continued relevance of the concept of “national art”. How did the émigrés change the national narratives? Why did so many Hungarian artists emigrate? While the very concept of emigration is related to the existence of nation-states, emigration is seen as a political act – free international movement of artists had not been seen as emigration before World War I. Relocation of artists, in particular after World War I did, if not in every case, express a political standpoint: they moved over to freer, artistically, financially, and intellectually unrestrained countries. The direction was mostly from Russia and Eastern Europe to Western Europe, the U.S., and Mexico. The great number of émigrés in the interwar period challenges the concept of national art historical narratives. If an artist, having been raised and educated in Hungary, chooses to live in France, Germany, or the US, to which country’s culture does s/he belong? Does artistic formation weigh as much as the new context that allowed him/her to develop as an artist? Can his/her achievements be seen originating from their country, are they reflecting the values of the new one? Museums designate artists to the country the citizen of which they died. Thus, Kandinsky was French, born in Moscow. Moholy-Nagy was American, born at Bácsborsód. This, however, does not answer the question, which is further complicated by later efforts to re-graft artists to the culture of their country of origin. Outlining patterns of emigration related to the time, the medium, and the adjustment to the new country, I will demonstrate the complications of re-grafting in the example of Victor Vasarely. |

|

| 19:00 - 20:30 |

Fogadás

|

|

2024-10-11

| Időpont | Cím: absztrakt/videó | Előadó |

|---|---|---|

| 10:00 - 11:00 |

Keynote Lecture: A Review of the Exhibition “Germany/1920s/New Objectivity/August Sander”, Centre Pompidou, Summer 2022: Sociological Aspects of the Interwar Years

In summer 2022, the Centre Pompidou devoted a major exhibition to the art and culture of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) in Germany, with the aim of re-reading the history of cultural production in the Weimar Republic, under the keyword “sachlich”, whose difficult translation into other languages points to the special nature of the concept. In addition to painting and photography, the project brought together architecture, design, film, theater, literature and music. Photographer August Sander’s masterpiece, Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century), established the motif of a cross-section through a society as a structural principle, as an “exhibition within an exhibition”. Together, these two perspectives opened up a broad panorama of German art, focusing in particular on the years 1925–1929, when Germany enjoyed a degree of economic stability. An aim was to highlight the dialectic between, on the one hand, a fascination with the achievements of the modern age (technological progress, standardization, etc.), and, on the other, a critique of cold, alienating functionalization. For the Hungarian film theorist Béla Balázs, who lived in Berlin between 1926 and 1931, the dispossessed human being had become a mechanized part of a system hostile to life. In a society increasingly under the sway of the capitalist imperative of rationalization, the transformation of man into a passive thing, his reification, became an essential feature of this new world, indeed a prerequisite for its existence. Based on the artworks in the exhibition and its two-part structure, this lecture seeks to shed light on the ambiguities of this new cold order, which, in the interwar years, particularly conditioned life in German metropolises. As Robert Musil summed up in 1930 in his great novel Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften (The Man Without Qualities), “One has gained reality and lost dreams.” |

|

| 11:00 - 12:40 |

Session 1 · Art and Revolution

Szekcióvezető: Szirmai Anna |

|

| 11:00 - 11:20 |

“A Beehive of Creativity“? Interwar Collaborations Through the Artists International Association

In 1933, the year Hitler took power in Germany and with half the British population living below the poverty line, radical artists’ group Artists International Association (AIA) formed in London. The group announced themselves as The International Unity of Artists Against Imperialist War on the Soviet Union, Fascism and Colonial Oppression, declaring that they would achieve their ends through creating ”propaganda” in the form of ”posters, illustrations, cartoons, book jackets, banners, tableaux, and stage decorations” spread through the press, lectures, meetings and exhibitions. The founding members’ idea for the group was shaped by direct experience of living in the Soviet Union and by the success of groups like Asso, which had formed in Germany in 1928. Numerous core AIA members had direct experience of migration. Commercial artist Misha Black, who hosted the group’s inaugural meeting, had arrived in London as a child, having migrated with his parents from the Russian Empire. Many other new members joined on arrival from central and eastern Europe after fleeing the Nazi threat, including German graphic designer FHK Henrion (arriving in 1936); Hungarian sculptor Péter László Péri (arriving in 1933); and Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka (arriving in 1938). Czech born philosopher Vilém Flusser, himself arriving in London in 1939, observed that ”If he is not to perish, the expellee must be creative… The arrival of expellees in exile evokes external dialogues, and a beehive of creativity spontaneously surrounds the expellee.” This process of working in dialogue across creative forms became a significant focus for newly arriving artists and designers joining the AIA. Discussing examples of AIA members’ varied projects, from banners to lithographs and exhibitions, this paper will explore how experiences of migration shaped not only AIA members’ affiliations and their politics but also determined both the form and focus of their resulting work. |

|

| 11:20 - 11:40 |

From Anti-Modernist Concepts to Marxist Theory. Conceptualising the Art of the Emigré in Interwar Art Criticism

The category of emigrant artists embodies a plethora of dual perceptions of the sending and receiving countries. Underlying epistemological concepts active in the discursive process producing representations of otherness, and specific administrative categories (foreigners, naturalised citizens, ”undesirables”, etc.) are combined with perceptions of citizens relocating as deserters of the nation-state, actors of national representation or upon their return, importers of knowledge. My paper examines professional authors writing about visual art, born in Hungary and active in Berlin and Paris in the 1920s, emigrants themselves, who contribute to historiographical narratives of contemporary art that are proposed to, among others, fellow emigrant artists to situate themselves within. The authors under study, Ernő/Ernst Kállai, Alfréd ”Durus” Kemény, and Emil Szittya, allow for a comparative approach to an overview of various genres (art history, criticism, social reports on artists) and platforms (periodicals [art journals, general interest magazines, party organs], editions of specialist art publishers [the series Probleme der neuesten Europäischen Malerei by Klinkhardt & Biermann]). They also represent modernist and anti-modernist historiographical theories of modern and avant-garde art that coexisted in the period. Szittya’s reliance on the concepts of national character and the Schicksaleidee, a theory postulating the existence of cultures as social entities and the conceptualisation of their political history as collective, deterministic biographies (originating in Oswald Spengler’s Der Untergang des Abendlandes [1918]) coincided with Kemény’s Marxist aesthetics. Kállai’s progressionist concept of art was, to some extent, informed by both national characteristics and the Marxist class theory. While examining these rich corpora and contrasting contemporary Hungarian/ German and German/French writings by the same author, I focus specifically on the conflicting or complementary politico-artistic narratives proposed to audiences in the sending and receiving countries to understand the categories of artistic and general (re)assimilation and the contrasting concepts of cosmopolitanism/ internationalism versus national/autochthone culture. |

|

| 11:40 - 12:00 |

“I Like the English so Much, as if They Were My Relatives”: Kokoschka’s Exile in London in 1938

In 1938, on the eve of the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, Oskar Kokoschka (Pöchlarn 1886 – Montreux 1980) took refuge in London, taking part in the international resistance in defense of freedom. From that moment he became a leading figure on the European intellectual scene, exploring mythology to find the common cultural ferment that united the societies of Europe. Kokoschka had entered Britain on a Czech passport, after Masaryk had helped him apply for Czech citizenship in 1935. This would later prove beneficial to the artist: in the panic of the summer of 1940, after the fall of France, thousands of German and Austrian refugees were classified by Parliament as “enemy aliens” and interned. The Czechs, on the other hand, were considered “friendly aliens”, with a government-in-exile in London led by Edvard Beneš; and although their movements in Britain were limited, they were otherwise left more or less alone. Kokoschka was thus in a good position to mobilize for the liberation of his anti- Nazi and Jewish friends, including artists, from internment camps, and for the total repeal of the laws against foreigners. This was in line with the policy of the so-called Free Austrian Movement and the Free German League of Culture, two refugee organizations in which he took an active part. In December 1941 he called for an end to the “scandal” of internment, which he denounced as “the skeleton in the closet of democracy”, and for internees to be allowed to contribute to the war effort. A few weeks before the outbreak of war, Kokoschka left London, which was becoming too expensive for him and his wife Olda Palkovská, and moved to the picturesque fishing village of Polperro, on the southern coast of Cornwall. His attitude toward the United Kingdom would always remain positive. This study aims to analyze the artistic, political, intellectual, and social networks that enabled Kokoschka to pursue his cultural-political activities — strong in his belief, always translated into his work, of the subversive power of painting. |

|

| 12:00 - 12:20 |

Louis Lozowick’s Stay in Berlin (1920)

Louis Lozowick (1892–1973) left his Ukrainian shtetl after an initial artistic apprenticeship in Kiev to join his brother in New York and become one of the most famous American lithographers. For a few decades his works were published across the magazines of the American left (New Masses), artistic modernism (Broom), and the Jewish diaspora (Menorah journal). Lozowick was both an illustrator and historian of the Yiddish visual world as well as of the European avant-garde and Soviet art, about which he continued to learn as he travelled several times to the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. The artistic process in his many works, which are mostly preserved in the American museums, is best understood through the lens of his autobiography Survivor of a Dead Age. In 1920, Louis Lozowick was in Berlin. He exhibited among the avant-gardes, frequented the Russian constructivists (El Lissitsky and Naum Gabo in particular), and took part in publishing projects: we find him around the magazine Albatros (see the attached photograph) but also in a work published in 1922 on Jewish graphic art by Petropolis Edition. My lecture will focus on Lozowick’s little-known involvement in these Berlin diasporic circles. Drawing on Lozowick’s memoirs and his personal fund in the national American archives of the Smithsonian Institute (where I spent a research trip in November 2023), I will try to shed light on a lesser-known aspect of the circulations between East and West through Lozowick’s point of view to highlight the special role of publishing houses and journals in building artistic networks in Berlin. |

|

| 12:20 - 12:40 |

Vita

|

|

| 12:40 - 14:00 |

Ebéd

|

|

| 14:00 - 14:20 |

Kávészünet

|

|

| 14:20 - 15:40 |

Session 2 · From Sociabilities to Integration – Institutions and Informal Contacts

Chair: Sz. Horváth Ágnes |

|

| 14:20 - 14:40 |

“The Secret of Caresses”: Visualising Queerness by Marcell Vértes in Interwar Paris

Marcell Vértes (1895–1961), often referred to as the most Parisian Hungarian painter, fled to Vienna after the fall of the Soviet Republic. There, he gained recognition for his drawing talent, winning numerous commissions for poster design, which eventually provided him with the financial means to continue his career in Paris from the early 1920s. The années folles in Paris offered Vértes great opportunities: a widening network of connections among artists and intellectuals (such as Colette, Jean Cocteau, Pierre Louÿs, Francis Carco, Maryse Choisy, Elsa Schiaparelli) provided him with social and cultural capital that not only enabled him to obtain commissions but also directed his artistic interests towards the depiction of the fashionable and interlope facets of urban modernity. Among these themes, queer subculture emerged as a subject of predilection for Vértes from the beginning of his Parisian years. In early twentieth century Paris, homosexuals, a transgressive part of the urban population and an emerging identity group, gained increasing social visibility: new venues and events of sociability appeared, and at the same time artistic representations explicitly thematizing the phenomenon multiplied. In this presentation, I will examine the metropolis as a space that not only attracts sexual minorities but also constructs queer subjectivities while shaping artistic sensibilities in this direction. Focusing on Vértes’ œuvre, I will analyze the strategies he employed to portray queer sociability and subjectivity. By contextualizing his work within the broader landscape of representations of same-sex desire during the interwar period, I aim to uncover the nuances of Vértes’s engagement with this theme and their resonance with the cultural milieu of his time. |

|

| 14:40 - 15:00 |

In Search of an Identity: Interwar Slovak Architecture at the Crossroads of Modernisms

During the interwar period, the lack of architectural education in the territory of present-day Slovakia motivated aspiring architects to seek education and professional guidance in neighbouring urban centres such as Vienna, Budapest and Prague. The primary aim of the proposal is to examine the motivations of three architects from this region to travel abroad to gain experience and expertise before establishing their own practices at home, and to assess the impact of these encounters. Dušan Jurkovič, Fridrich Weinwurm, and Emil Belluš represented different forms of dialogue between historical and modern principles in interwar Slovak architecture, based in part on their educational backgrounds. We will also discuss how their years of study and the multicultural environment of the metropolises of the former monarchy influenced their architectural strategies and how they contributed to the formation of the heterogeneous character of interwar architectural practice in the territory of present-day Slovakia, which was gradually established in a continuous dialogue with the wider Czechoslovak and regional context. |

|

| 15:00 - 15:20 |

Critical Collaborations in Central Asia

What was it like to be a foreign artist on the peripheries of the Soviet Union in the 1930s and early 1940s? This paper studies the political networks and aesthetic tactics of Soviet internationalism that Hungarian communist artists used in Central Asia to secure commissions and pursue their creative work despite lacking local language skills and often struggling even with the Russian language. Tashkent, Frunze (today Bishkek), and Alma-Ata (today Almaty) became especially bustling urban centers in the early 1940s, when Soviet and non-Soviet citizens alike were evacuated to the Soviet Central Asian republics during World War II. The Hungarian-born artist Jolán Szilágyi (1895–1971) and filmmaker and writer Béla Balázs (1884–1949) were among the foreigners who arrived in Frunze and Alma-Ata, respectively, in the fall of 1941. With their first-hand experience of fighting against Nazism in Berlin throughout the 1920s, both Szilágyi and Balázs were eager to battle against the Nazi enemy once again, branding themselves as anti-fascist artists. Yet evacuation to Central Asia posed severe obstacles to their political art making. As her surviving correspondence attests, Szilágyi repeatedly complained to the head of the Hungarian Section of the Comintern, Mátyás Rákosi, that she “was forced to relative muteness” in Soviet Kirghizia, having close to no opportunities and means to use the expertise she had gained in producing anti-fascist and anti-capitalist visual satire in Weimar Germany. Similarly, Balázs desperately tried to connect with Rákosi as his primary political contact and resource. I will analyze the unique collaborations that emerged between Rákosi and Hungarian artists such as Szilágyi and Balázs in the early 1940s, highlighting how the leader of the Hungarian diaspora offered his support to artists by securing them modest funds, supplying them with Hungarian-language political materials, and offering his critical feedback on their artistic work. |

|

| 15:20 - 15:40 |

Vita

|

|

| 15:40 - 16:00 |

Kávészünet

|

|

| 16:00 - 17:30 |

Session 3 · Transfers to the Sending Country

Szekcióvezető: Őze Eszter |

|

| 16:00 - 16:20 |

Migration, Return, and Exile: The Jewish Artists of the Romanian Avant-garde

This lecture will present the impact of temporary migration to Western European countries such as Germany, France and Switzerland in the interwar period on the artistic practices of several Jewish artists of Romanian origin and on the course of the avant-garde in Romania. The presentation will focus on the trajectories of several artists that were part of the same social circles, some very well-known while others who will be introduced here for the first time, such as Marcel Iancu, Victor Brauner, Jacques Herold, Hedda Sterne, Tristan Tzara, M. H. Maxy, Sigmund Maur, and several others. The lecture also analyzes how the effervescent cultural atmosphere of interwar Romania was created through the social and cultural capital these artists developed through artistic exchanges established while they were abroad. These artists, upon their return to Romania, initiated publications that promoted to the Romanian public the artistic movements with which they had connected in the West, and their pages became platforms for maintaining the artistic networks formerly established. As Jews, these artists did not benefit from any government support to travel abroad, but had to rely on their personal resources and connections. Once World War II broke out and many of these artists managed to escape fascist Romania, while others decided to remain in the country, the respective influence of each on Romanian artistic trends also changed accordingly. During this period, those that migrated to France were absorbed through their networks and relations in the French avant- garde, several becoming recognized as representatives of France later on. Likewise Marcel Iancu in Israel and Hedda Sterne in the United States, in effect leaving few formerly avant-garde artists behind in Romania, who after the war integrated themselves in the state art of the communist society. In conclusion, I will address the impact of this geographic separation (which is inherently also representative of an ideological separation) on the formation of the art historical canon in Romania and abroad. |

|

| 16:20 - 16:40 |

Theatre Exhibitions as a Mirror of International Impregnation of Hungarian Emigré Artists. The International Theatre Exposition, New York, 1926

Three special exhibitions of theatre designs were organised in the 1920s which served to present the avant-garde ideas in performance art. The first one was held in Vienna in 1924, the second was the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925 where the stage design received outstanding attention and the third was the International Theatre Exposition in New York in 1926. This lecture focuses on the New York show with reference to the Paris events. The three exhibitions were displayed in different cities, with different backgrounds and organising committees and they represented different missions. The common denominators between these shows are not only Friedrich Kiesler, the Austrian born architect and theatre designer, who was the curator of the exhibitions in Vienna and New York and also the Austrian pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris, but also the fact that numerous Hungarian émigré artists’ works were included in these shows. Friedrich Kiesler was a practicing designer with a really progressive philosophy about the new forms of theatre and he included all of the avant-garde ideas appearing in the 1920s relating to theatre techniques and architecture into the shows he curated. However these exhibitions are not only interesting because of the curator but also because the presence of the Hungarian émigré artists, especially in the New York exhibition. The visitors could see the plans of Marcel Breuer, Vilmos Huszár, László Moholy-Nagy, Ladislas Medgyes, and Farkas Molnár amongst the figures of the international avant-garde such as Fortunato Depero, El Lissitzky, or Oscar Schlemmer. As part of my current research, this presentation focuses on how these Hungarian artists related to the so-called avant-garde theatre ideas and how they participated in those artistic groups or became attached to personalities who were the catalysts of these innovative tendencies. The study of the exhibitions, especially the New York show, provides the possibility not only to present the Hungarian artists’ experiments in this field but to draw inferences relating to their impregnation to absorption into the international scene. My aim is to draw up a network of these artists and show how their work became embedded as equal part of these reformist tendencies. |

|

| 16:40 - 17:00 |

Gyula Zilzer in Paris (1924–1932)

My research focuses on Gyula Zilzer, a Hungarian artist linked to New Objectivity, a movement rooting in Weimar Germany and then spreading throughout the whole European continent and overseas as well, becoming established in the Americas. Gyula Zilzer (1898–1969), a lesser known though very versatile Hungarian artist – who was a painter, graphic designer, illustrator, printmaker, and movie set designer – lived most of his life outside his native country, Hungary. He briefly left Hungary in 1919, first to Italy and then to Munich for his formative years at Hans Hoffman’s School of Fine Arts. In 1924 Zilzer permanently settled in Paris. The Parisian period lasted eight years and proved to be very fruitful for Zilzer who met a lot of people and established relationships of professional and personal importance. At the time, Paris was the stronghold of avant-garde art: leftist painters, writers, poets, thinkers, film directors, and photographers found a home there, and the city became their source of inspiration. Zilzer was welcomed by Hungarian émigré artists, e.g. Lajos Tihanyi, Béla Czóbel, Béla Uitz, Marcell Vértes, and Gyula Illyés. Zilzer’s long-time friend from Budapest, photographer André Kertész joined them in 1925. The main haunts of the Hungarian émigrés were Café du Dôme and Rotonde in the Montparnasse district. In addition, he worked together as an illustrator at newspapers L’Humanité and Clarté with leftist poet and writer Henri Barbusse and pacifist writer Romain Rolland. Through these acquaintances Zilzer, a genuinely leftist artist himself, joined the international network of anti-fascism. 1932 marks the end of Gyula Zilzer’s time in France before he left to the United States. In that year he also produced the lithograph album titled Gáz, his most successful work in Paris. The album imagines a gas attack on Paris and the catastrophic consequences are depicted in twenty-four sheets. The album became an important artistic product in the anti-war movement. |

|

| 17:00 - 17:30 |

Vita / Záró gondolatok

|

|